The Productivity-Pay Gap Explained

What’s the deal with the divergence in productivity rates and income over the last several decades?

Since the 1970s, the increase in company productivity rates has not resulted in an increase in employee wages.

This occurrence is referred to as the productivity-pay gap.

The productivity–pay gap has many causes and differs at the industry level (the gap is higher in some industries than in others).

This article will help you debunk various myths and understand the core issues surrounding the productivity–pay gap.

So let’s dive right in.

What is the productivity–pay gap?

The productivity–pay gap is the difference between labor productivity and employee wages. In other words, it’s how much workers are producing per hour worked compared to how much they actually earn for those hours. Ideally, when productivity grows, wages should grow simultaneously.

What is productivity?

Before we discuss the relationship between productivity and median wages in more detail, we should define productivity.

There are several variations of the definition, depending on the industry — but we’re currently interested in the economics definition, which goes as follows:

Productivity is calculated as a ratio of gross domestic product per hour worked and is a measure of output per unit of input.

Simply put, productivity shows how efficiently one completes a certain task.

Therefore, we are talking about a person’s productivity rate as measured on a daily basis.

For a worker to be productive, they must be motivated either by internal or external factors.

Internal factors imply that a person is motivated to perform an activity for its own sake because it’s enjoyable and pleasurable to them. So, the behavior itself is the reward.

On the other hand, external factors include financial incentives, public recognition, or status, for example.

How does productivity affect wages?

When productivity increases, company profits increase as well — and all interested parties (should) benefit from that.

Productive workers have a higher ability to focus and know when it’s time to take a break. In other words, their time management skills are better, resulting in a more suitable work-life balance.

When it comes to the workplace, the stronger the initiative on a company level and the higher the rewards, the more likely employees are to be engaged and motivated to find other ways to improve their skills.

This is what should happen in practice, at least, but as we can see, that’s not always the case. The productivity-pay gap shows us that there are events when high productivity doesn’t necessarily result in higher wages.

Let’s take a look at how the productivity vs. wages relationship has changed over time.

History of the productivity-pay gap in US economy

If we look at the history of the US economy, the productivity-pay gap wasn’t as disproportionate as it is today. According to an Economic Policy Institute (EPI) study, between the late 1940s and 1960s, productivity and pay grew almost in the same direction — workers were getting higher wages when their productivity increased.

However, that gap changed a lot in the late 1970s (for various reasons, which we’ll discuss later in the text). This means that since then, employee wages haven’t increased as much as their productivity has.

Interestingly, productivity rates grew rapidly between 1979 and 2024, while the hourly compensation for the same period decreased immensely, as shown in the table below.

| Year | Productivity growth rate | Hourly compensation growth |

| 1950s–1960s | 33.1% | 31.2% |

| 1960s–1970s | 30.4% | 23.6% |

| 1970s–1980s | 12.9% | 6.4% |

| 1980s–1990s | 10.2% | -2.4% |

| 1990s–2000s | 16.6% | 7.4% |

| 2000s–2010s | 26.1% | 14.1% |

| 2010s–2020s | 14.8% | 10.8% |

| 2020s–2024 | 4.9% | 2.1% |

| Total growth: 1950 — 2024 | 261.7% | 122.0% |

We can conclude that in the modern era, as worker productivity grows, workers don’t seem to receive their fair share despite their contributions.

It would be easy to rush to conclusions and blame it all on a broken economic system where the richest are becoming richer — but bear in mind, this is only part of the reason.

Reasons for the wages–productivity gap

There isn’t a single definitive answer to why the wages-productivity gap occurs, especially if we want to speak about society as a whole. Therefore, here are some of the reasons behind the productivity-pay gap.

#1: Diversity of industries

First, the disconnect between employee productivity growth and wage growth may differ across industries. For example, we hardly see that gap in tech and finance, where employees’ productivity grows mainly together with their wages.

According to this ADP report, in the Bay Area region, technology companies such as Google, Apple, Meta, and Nvidia offer high wages to top performers, paying their workers more than $500,000 annually. At the same time, industries such as retail and hospitality experience still wages, no matter the productivity increase.

#2: Technological advancement

Even though the automation of many processes and the presence of AI have had a major impact on productivity growth — the ones who reap the benefits are mostly business owners and executives.

From the beginning of the 1990s to the 2010s (based on the EPI study above), the biggest increase in productivity of more than 40% happened due to the presence of the Internet and computers.

However, such a rise in productivity due to technology changes (especially AI) didn't result in equal pay rises, making CEOs and top executives high-income earners, unlike the rest of the workforce.

#3: Job globalization

Another factor that influences the disproportion between worker productivity and wages is the trend of shifting production and jobs to low-labor-cost countries. This further results in still or reduced wage growth in higher-wage countries.

For instance, industries such as clothing, electronics, cars, and many others have moved their production to countries like China, India, Vietnam, and Eastern European countries. There, the wages are much lower than in the US, Germany, or any other more economically developed country.

While companies reduce labor costs this way, they limit the possibilities for wage growth in higher-cost countries, creating the productivity-pay gap once again.

🎓 How To Calculate Labor Cost + Labor Cost Calculators

#4: Declining unionization

US workers in unions used to get higher wages as the economy prospered. Now that unions are losing power — unions in private sectors fell from 35% in the 1960s to just 6% in 2023 — we have a significant decline in unionized workers’ compensation, too.

Likewise, research by the Union Membership and Coverage Database in 2024 shows that the number of workers covered by a collective bargaining agreement fell from 27% in 1979 to 11.6% in 2019. In other words, workers whose rights (including wages) were once protected by unions are now left with lowered median wages, despite the increases in productivity.

Namely, a typical or median worker lost $1.56 per hour between 1979 and 2017, which is $3,250 a year for a full-time worker.

#5: Lack of adequate labor laws

Another significant factor contributing to the productivity-pay gap is either the complete lack of labor policies or the fact that the existing ones are rarely updated. A lot of them don’t keep up with inflation or any other economic conditions in a state.

Minimum wage laws in certain states have remained unchanged for decades. For instance, the minimum wage in Georgia is $5.15 (the lowest in the US) — and this rate has remained the same since 2002.

Although a lot has happened in the last 23 years, including financial crises, inflation, technology rises, etc., the minimum wage has remained unchanged no matter the increased employee output.

This is just another example of why the productivity-pay gap happens — but now let's dive into the details, starting with the longitudinal study of the productivity–pay gap.

A longitudinal study of the productivity–pay gap

With the abundance of factors that influence the pay-productivity gap, it’s already challenging to determine its exact ratio precisely.

Not understanding the big picture and how everything is connected creates an additional issue — misconceptions and even urban myths about the topic.

One major reason for emphasizing the gap and not adjusting the ideal ratio in accordance with several crucial factors, including automation, is the story about middle-class stagnation. Don’t get us wrong — inequality does exist — but this particular issue is a complex one.

Let's see what economists have to say about the productivity-pay gap and further examine some major methodological flaws in their reasoning — via a longitudinal EPI study of the productivity–pay gap.

We’ll dissect the following topics:

- Productivity–pay gap: methodological consideration, and

- What role automation plays in the productivity–pay gap.

Productivity-pay gap: Methodological considerations

The years 1979 and 2019 are interestingly suitable for comparison, marked as years with low employment rates — and the whole 4-decade period is one of rising inequality.

Some of the explanatory factors EPI emphasizes are the following:

- Inequality of compensation,

- Loss in labor's share of income, and

- Divergence of consumer and output prices.

We've also already mentioned many other aspects due to which results can vary. Another issue is the different approaches of the economists — and the Consumer Price Index changes over time.

What do economists think of the productivity-pay gap?

Opinions about this question vary among economists, and many would argue that the main reason is their political orientation.

There's a group of neoclassical economists who blame technology for the pay-productivity gap. This argument is called “skill-biased technological change” and has many flaws at its core — it does not take into account other major factors we've previously mentioned (job globalization, diversity of industries, etc.).

Technology and automation serve the purpose of improving productivity — essentially increasing the minimum wage per hour.

To debunk the “skill-biased technological change” notion, the Economic Policy Institute pointed out how the declining wage gap from 1987 to 2017 is inconsistent with the skills–gap explanation. In said period, the group of more educated middle-wage earners didn't see any advantage over the low-wage earners, which debunks the whole argument.

Moreover, even the wages of high-skilled workers didn't see a notable increase, meaning the level of education can’t be a conclusive factor in analyzing the pay–productivity gap.

The productivity-pay gap: the most significant factors

According to the MIT economist David Autor, cited in another relevant EPI analysis, the pay–productivity gap is a combination of 2 major forces driving inequality, including:

- The rate of growth of educational attainment — which slowed down in the 1980s, and

- The direction of technological change — which increased the value of abstract reasoning of critical thinking, judgment, and creativity.

Inequality and divergence were discussed in a similar way in a paper published by the Peterson Institute for International Economics. This is relevant because several additional factors are included as the major drivers of the productivity–pay gap, including:

- Globalization,

- Labor market institutions such as unions, and

- Market power.

Following the same logic, Bloomberg also covered this important topic. Their article presented interesting results from a study by Stansbury and Summers — they found that the correlation between productivity and wages does exist — even though it isn't possible to categorize such a complex issue in a simple economic model.

Why was their approach innovative?

Unlike the vast majority of economists, they didn’t focus solely on the graph depicting the long-term trend — instead, they examined short-term changes in the relationship between productivity and wages.

The examined periods were no longer than 5 years, and the analysis of the results proves that when productivity levels rise, wages tend to increase as well.

What role does automation play in the productivity–pay gap?

Since the late 1980s, automation has been one of the most controversial topics regarding the productivity-pay gap.

One thing is for sure — technological change in the workplace and globalization driven by it not only influenced the gap but also created another closely related gap. We’re talking about wage inequality between the less and the more educated people.

But we can't blame technology and say that the bias is in favor of workers with college degrees.

This other gap has always existed between high-level employees (or the 10th percentile) and the rest.

That being said, there's a significant difference in the impact of automation on the productivity–pay gap across industries, even specific sectors within a specific industry.

According to a McKinsey Global Institute report, as much as 30% of work hours in the US could be completely automated, blaming AI for the rise of this trend.

We already touched upon the jobs that underwent automation in the past. So, these are the industries that have lately been at the highest risk of transformation:

- Manufacturing and factory workers (Robots),

- IT (Data security, Process automation),

- Finance (Trading, Advisory services),

- Marketing (AI chatbots),

- Healthcare (Wellness wearables),

- Transportation (Self-driving vehicles), and others.

Moreover, according to the International Data Corporation (IDC), AI investments will grow even more. Namely, by 2028, AI spending in the US will reach $336 billion.

So what's the logical conclusion?

Automation brings change and implies the need for different skills for the future — but that's what progress is all about.

Important distinctions in the productivity–pay gap

The productivity-pay gap can significantly vary, such as by the industry type, which we have previously mentioned.

But, we can also approach the topic by analyzing specific factors such as the following ones:

- Job level,

- Country, and

- Gender.

#1: The productivity–pay gap by job level

An important point to consider is the wage inequality gap. This means that only the highest earners experience wage growth, unlike, for instance, entry-level jobs.

The latest EPI analysis on wage inequality indicates that the situation has significantly changed for the top 1%, 10%, and 90% of earners since 1979. Here’s an overview:

- Top 0.1% earners make up the wealthiest individuals in the world,

- Top 1% earners are individuals who earn more than 99% of the population,

- Top 10% earners have more earnings than 90% of the population, while

- The bottom 90% earners are those whose income falls below the top 10% (middle and lower-income earners).

Since 1979, there's been an established pattern of faster annual wage growth among the top 1% and even faster for the top 0.1%.

Let’s examine how different job levels can influence the productivity–pay gap, comparing 2 extremes: the bottom 90% of earners and the top 1%.

-

Bottom 90% earners productivity–pay gap

-

Top 1% earners productivity–pay gap

The data from the said EPI analysis shows the disparity in wage growth for the bottom 90%, whose annual wages grew by almost 44% between 1979 and 2023.

To help you grasp the concept better, we'll present the monetary value of these average wages per year.

| Year | 1979 | 1989 | 2000 | 2007 | 2019 | 2022 | 2023 |

| Bottom 90% earners | $29,953 | $30,927 | $34,618 | $36,570 | $40,988 | $42,658 | $43,035 |

For instance, one bottom 90% earner, whose salary was $29,953 in 1979, earned $43,035 in 2023. Considering that’s a period of more than 40 years, and taking into consideration the economic conditions, the bottom 90% of earners saw a modest pay growth.

The implication is that the pay–productivity gap was significantly lower for this group, making wage inequality perhaps an even greater issue.

Now, compared to the bottom 90% of earners, the annual earnings in the upper 1% are much higher, to say the least. As opposed to the 44% in the bottom 90% earners, the top 1% earners’ annual wages surged by a whopping 353% in the same period.

Here’s a breakdown of 1% earners’ annual wages between 1979 and 2023:

| Year | 1979 | 1989 | 2000 | 2007 | 2019 | 2022 | 2023 |

| Top 1% earners | $281,932 | $469,603 | $699,846 | $753,063 | $789,317 | $820,863 | $794,129 |

Even though the wage gap was already quite notable back in 1979 — the top 1% earners used to earn over 9 times more than the 90% earners — it skyrocketed in 2023. In 2023, the top 1% earning workers earned more than 18 times the wages of the bottom 90%.

The difference in wages tells us that, no matter the growth in productivity, most of the profit goes to top earners (as discussed in the Reasons for wages–productivity gap section).

#2: The productivity–pay gap by country

Different countries focus on different industries, which, as we've mentioned, can be another reason for the gap.

Why would the region matter for the productivity–pay gap?

The explanation is that the growth path of a certain region depends on the pre-existing industries originally developed due to geographical factors such as climate, natural resources available, etc.

So, while the implementation of changes and industrial transition may have happened simultaneously, the results are still different for rural and urban areas, not to mention different continents.

Urban areas are more populated, have higher living standards, and tend to attract more technologically advanced sectors such as finance, real estate, IT, etc. For this reason, it's safe to conclude that the wages of urban-area residents are higher — making the productivity–pay gap smaller.

Another crucial consequence of the abovementioned, as well as many other geopolitical factors, is the variation in the average number of hours worked by country, which also impacts the pay-productivity gap.

For example, full-time employees in the US still work more hours per year than full-time employees in Europe. For example, the norm for the workweek in the US is 40 hours, while it’s 35 hours in France.

If we didn’t take into account any other factors, the logical conclusion would be that people in Europe are more productive. But of course, as we've seen, it's not nearly as simple as that.

Embracing the 4th industrial revolution seems to be one way for a country to build resilience to failure, as technology and other kinds of experimentation lead to higher productivity, wages, and living standards.

Apart from measuring individual and team productivity, you can actually measure a country’s productivity. If you’re wondering how one can do just that, the answer lies in:

- Gross Domestic Product (GDP) — the monetary value of goods and services within a certain country, while purchasing power parity determines the relation between economic productivity and living standards of different countries, and

- An average worker’s productivity per person per hour(PPP) — shows how much money workers contribute to the country’s economy per hour.

The top 10 most productive countries

Let’s examine the latest list of the top 10 most productive countries and try to establish a pattern of major economic sectors and industries.

So, the list you see below actually reflects an average worker’s productivity per person, per hour (PPP), and GDP per capita, along with annual work hours, based on 2022 data.

| Rank | Country | Productivity per person, per hour (USD) | GDP per capita (USD) | Hours worked (per year) | The biggest economic sectors | |||||

| 1. | Luxembourg | $97.51 | $134,754 | 1,382 | Finance, information and communication, logistics, and tourism. | |||||

| 2. | Ireland | $59.98 | $106,456 | 1,775 | Information and communication, professional transport, and hotels. | |||||

| 3. | Norway | $55.50 | $79,201 | 1,427 | Oil and gas production, hydropower, fish, forests, and minerals. | |||||

| 4. | Switzerland | $50.43 | $77,324 | 1,533 | Finance, banking, manufacturing, and agriculture. | |||||

| 5. | Denmark | $47.42 | $64,651 | 1,363 | Trade, transport, and medical equipment. | |||||

| 6. | Netherlands | $45.02 | $63,767 | 1,417 | Finance, trade, transport, and energy. | |||||

| 7. | Germany | $42.93 | $57,928 | 1,349 | Finance, telecommunications, tourism, and transport. | |||||

| 8. | Sweden | $41.07 | $59,324 | 1,444 | Finance, insurance, real estate, retail, and transport. | |||||

| 9. | Austria | $40.51 | $58,427 | 1,442 | Finance, insurance, tourism, construction, and vehicles. | |||||

| 10. | Iceland | $40.22 | $57,646 | 1,433 | Tourism, finance, manufacturing, fishing, and renewable energy production. | |||||

Here we can see insights into the productivity–pay gap beyond just the US perspective. What we can conclude is that productivity doesn’t always result in higher wages, which countries like Luxembourg and Ireland show us. Namely, those countries have high productivity per hour — but that’s not followed by equal wage distribution (only top earners reap the benefits, tech and finance especially).

On the other hand, Scandinavian countries like Norway, Denmark, and Sweden show high productivity and more equality in terms of wages due to their strong unions and labor rights (which a lot of countries, including the US, lack today).

Nevertheless, the disproportion between productivity and wages is a relatively global issue, more obvious in some countries than others (such as Norway, Denmark, etc.). Factors such as labor laws, economic structures, and similar factors also play a critical role in how profit is shared.

#3: The productivity-pay gap by gender

When it comes to the main reasons for the very existence of the pay-productivity gap, we can’t ignore the “gender pay gap.”

The gender pay gap is the percentage by which hourly wages differ for men and women, being lower for the latter.

To provide a relevant example, here’s a shocking detail. As pointed out in another EPI analysis on the gender pay gap — women were paid 21.8% less than men in 2023.

Data from 2023 state that women who are full-time workers earned 83 cents for every dollar earned by men. In other words, full-time working women earned 83% of what men earned in 2023.

Moreover, there are 2 other discriminatory factors impacting the gender pay gap — age and race.

The same research shows that Latinas are among the lowest-paid women workers, with a median salary of $43,880. Women of color earned $50,470 in 2023, while caucasian women earned $60,450. At the same time, caucasian men’s median salary was $75,950.

It also appears that women’s educational attainment has exceeded men’s in the US, while the wage gap will continue to linger. In fact, the U.S. Census Bureau research from 2024 shows that 47% of women aged 25 to 34 have at least a bachelor’s degree, compared to 37% of men.

Objectively, there’s no room for this kind of discrimination in the modern age, as women are just as valuable as men. This goes especially for working mothers, as the scope of their responsibilities requires perfecting their time management skills.

The truth is out there, and the conclusion is that the productivity-pay gap does exist, no matter the educational attainment women achieve. Still, overcoming the gender wage gap could promote fairness and increase economic productivity, too.

Economic and policy implications of the productivity–pay gap

Last but not least, we want to devote this section to the effects that the productivity-pay gap has on the economy and government policies.

Economic implications

The phenomenon of high productivity and still wages can have far-reaching effects on the economy. Here are some of the implications:

- Poor living standards — When workers experience stagnant wages, their purchasing power also declines over time. They can’t keep up with the prices, resulting in poorer living standards.

- Slow economic growth — If the said workers experience stagnant wages and their purchasing power drops, this trend can affect the whole economy of a country. Since consumption is a major portion of the US economy, consumer spending on goods and services accounted for 68% of GDP growth in 2024. Therefore, low consumption would result in economic decline, too.

- Wage inequality — As mentioned above, the productivity-pay gap can also result in differences in wages, benefiting higher-income workers more.

- Increased government budget spending — When workers’ wages remain unchanged for a long period of time, these workers turn to public social programs more often, such as cash assistance, health insurance, housing subsidies, etc. As a result, a country’s budget shrinks, bringing higher taxes and debt, too.

Policy implications

Apart from economic implications, the productivity-pay gap can have certain effects on government policies and regulations. Here are some of them:

- Minimum wage — The gap between productivity and wages may also result from a country’s stagnant minimum wage, which is not adjusted to inflation to ensure fair compensation. Namely, the federal minimum wage in the US has been $7.25 since 2009. While some states adopted the federal minimum wage as their state minimum wage, other states adjust the minimum wage periodically, such as California (from $16/hour in 2024 to $16.50/hour in 2025).

- Progressive taxes — When an employee’s income increases, their tax rates increase simultaneously. At the same time, if an employee earns less, their income tax rates are lower. Now, progressive taxes can have a positive effect on lowering the productivity–pay gap. Since top earners must pay higher taxes, that income can be used to fund public services or programs, benefiting typical workers as well.

- Exploiting low-wage workers — Workers in service industries or manufacturing often don’t benefit from productivity growth but instead work more, hinder their work-life balance, and stay paid the same.

- Labor unions — Anti-union practices and a lack of union rights also impact the huge gap between productivity and wages. We’ve discussed how this trend lowers the hourly wage of a typical worker in the US, but countries like Sweden and Belgium have lower wage inequality thanks to their union memberships. The US can definitely look upon them since, for example, as much as 90% of Sweden workers are covered by collective bargaining agreements, contributing to equal wage distribution.

- High top-earner wages — We’ve already discussed how top earners earn a staggering 18 times more than typical workers in the US, creating an enormous gap in wage distribution.

The productivity–pay gap significantly impacts both economic and government policy levels in the US. From an economic perspective, it influences income inequality, poor purchasing power, and economic decline. From a policy perspective, it may call for higher wages and increased labor rights.

Reducing the gap between wages and productivity may benefit both a country's economic stability and stronger labor protections.

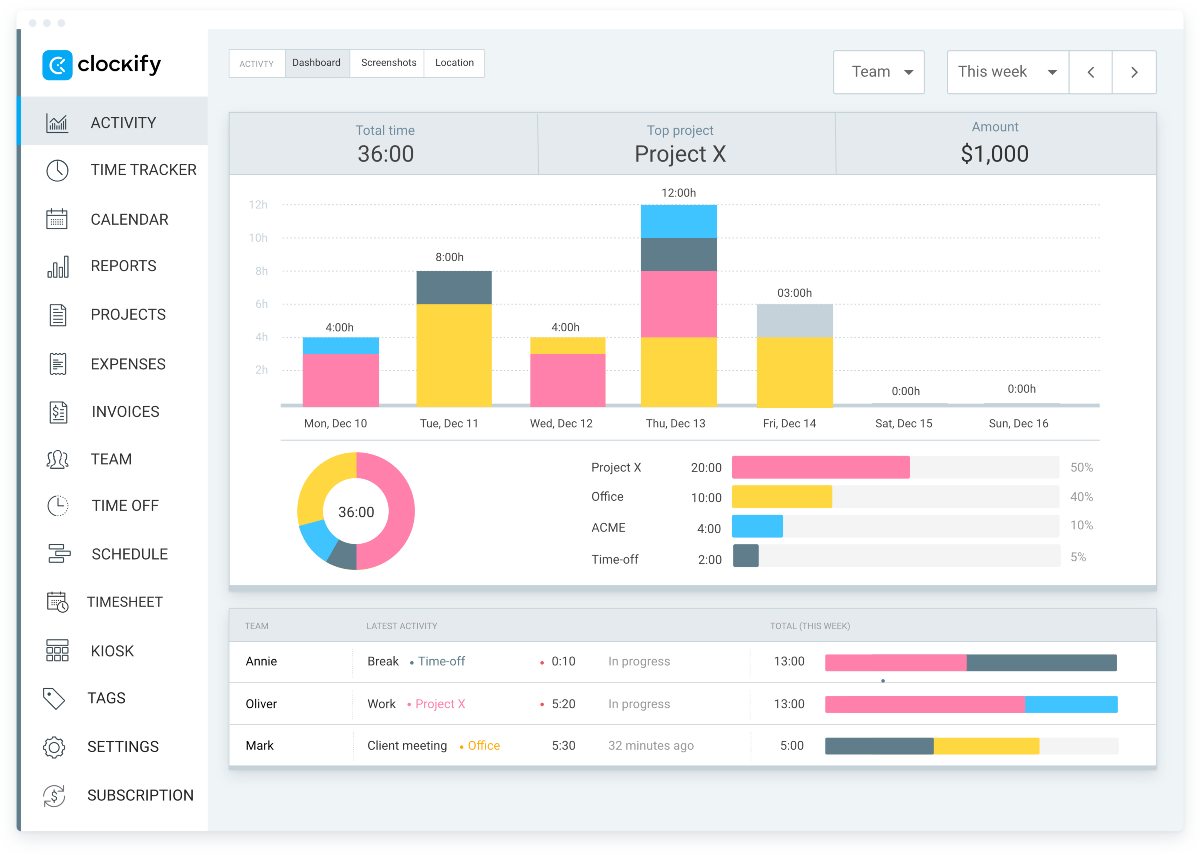

Create a fair and more transparent work environment with Clockify

To make sure your employees are compensated fairly and timely, you should opt for a tool that you can rely on — like Clockify.

Primarily a time tracking app, Clockify is used by millions around the world. You can use the simple software to:

- Track work hours spent on tasks, projects, or clients,

- Track employee performance reliably,

- Allocate tasks and projects evenly across the organization,

- Stay compliant with labor laws and regulations,

- Track payroll, and much more.

As an employer, you can detect pay disparities by tracking and analyzing the time your team spends on certain tasks, projects, or clients. In fact, Clockify’s rich reporting capabilities offer detailed insight into your team’s productivity.

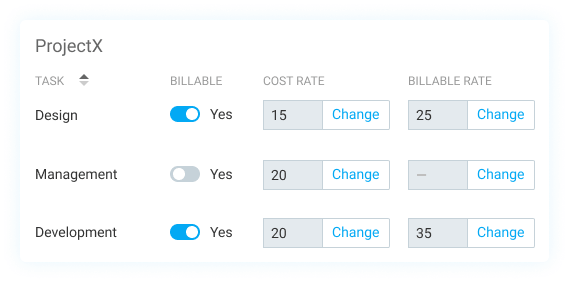

All your employees need to do is track their time, which will leave you with information such as who worked on what, for how long, whether that time is billable, and much more.

Without much trouble and technical knowledge, you get to see everything that’s happening in your organization.

Not to mention that Clockify makes sure your employees are paid fairly and timely.

While they need to track their time (choosing from different time tracking methods), you set hourly rates, and the app does everything else automatically.

Finally, Clockify allows you to export payroll reports either in PDF, CSV, or Excel formats.

Break the chain of the productivity–pay gap and ensure fair pay across your organization.